Everyone craves pleasure, but few know how best to obtain it and at what cost. Surprisingly, some of the most useful advice comes not from modern psychology but from a 2,000-year-old philosopher. Epicurus, known today as a decadent gourmand (witness the website named after him), was in fact less hedonist than “tranquillist.”

Yes, he advocated a life of pleasure but not as we typically think of the word. For Epicurus, pleasure consisted not of a presence (of anything) but an absence—a complete lack of anxiety. “It is better for you to lie upon a bed of straw and be free of fear, than to have a golden couch and an opulent table yet be troubled in mind,” he said.

We allegedly live in a golden age of pleasure. So many tantalizing options lie just a click away: gourmet food, memory-foam mattresses, smartwatches.

Pleasure decoys, all of them, Epicurus would say. Beyond a certain point, Epicurus believed, pleasure cannot be increased—just as a bright sky cannot get any brighter—but only varied. That new pair of Louboutins or Apple Watch represents pleasure varied, not increased.

Yet our entire consumer culture is predicated on the assumption that pleasure varied equals pleasure increased. This faulty equation causes needless unhappiness.

Epicurus thought a lot about a question we don’t ponder very often: How much is enough? The answer, he concludes, is “less than you think.” He would surely approve of the FIRE movement, and couples scrupulously downsizing so they’re able to retire early. “One must regard wealth beyond what is natural as of no more use than water to a container that is full to overflowing,” Epicurus said.

Though he lived centuries before the advent of economics, Epicurus understood intuitively the concept of “true cost.” Every pleasure, he believed, comes with hidden costs—not monetary but psychological. Consider a five-course meal at the French Laundry. Yes, you enjoyed the Pacific Wild King Salmon Terrine—the pleasure was real—but now it is gone, and you crave it again. You have outsourced your happiness to the Salmon Terrine—and to the fisherman who caught it, the restaurant that serves it, and the bull market that enables you to afford it.

There’s nothing wrong with a fine meal or a shiny new Tesla, Epicurus would say, as long as you don’t grow dependent on these bonbons—or, worse, get stuck on the “hedonic treadmill.” This quirk of human nature explains why that third crème brûlée never tastes as good as the first or second and why the new car that thrilled you on the test drive bores you after a month on the road. We acclimate to new pleasures, rendering them neither new nor quite as pleasurable.

Epicurus found a way off the hedonic treadmill. We can reason our way to pleasure, he thought, provided we do the math. Let’s say you live in suburban New York and are considering going to the city to catch a Broadway show (This is a post-pandemic scenario, of course.) On one side of the ledger is the pleasure of seeing the show. On the other side, is the cost of the tickets, the hassle of the traffic and, more insidious, the risk of becoming hooked on Broadway shows.

Epicurus’s pleasure calculus demands we tally our pleasures in their totality. Certain pleasures might lead to future pain and thus should be avoided. The pain of lung cancer outweighs the pleasure of smoking. Likewise, certain pains lead to future pleasure and thus should be endured. The pain of the gym, for instance.

The Epicurean life may not sound like much fun, but it is. The philosopher’s followers, ensconced behind the walls of their garden enclave in ancient Athens, lived a simple life but one punctuated by lavish feasts. They knew that luxury is best enjoyed intermittently, and welcomed whatever goodness came their way.

That goodness usually came in the form of an experience, not material goods. The ancient Epicureans were on to something. Several recent studies found we receive a greater happiness boost when we spend money on activities, rather than possessions. Better to take that trip to Belize than to buy that Rolex.

Don’t sweat the math, says Epicurus. Nature has you covered. She has made the necessary desires easy to obtain and the unnecessary ones difficult. Bananas grow on trees. Teslas don’t. Desire is nature’s GPS, guiding us toward the highest pleasures and away from the empty ones.

Friendship, Epicurus thought, is life’s greatest pleasure, especially during mealtimes. To eat and drink alone is “to devour like the lion and the wolf.” The meal need not be gourmet, either. With the right mindset, and in the right company, he said, even a simple pot of cheese is transformed into a feast.

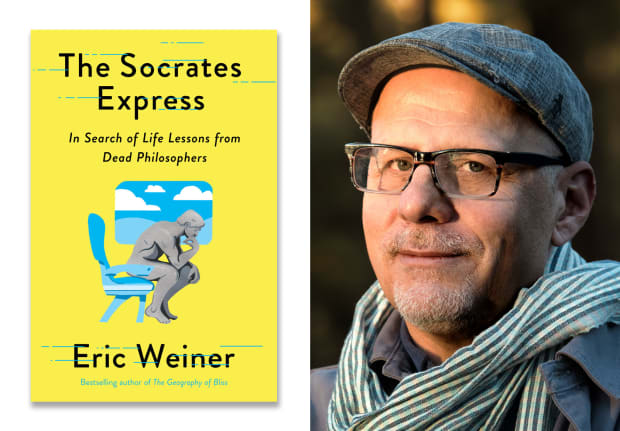

Eric Weiner is the author of “The Socrates Express: In Search of Life Lessons from Dead Philosophers. “

Now read: This is how your neighbors are preventing you from becoming a millionaire

Also: You’re saving all wrong if you die with a pile of money

And: The most successful way to make financial changes stick is one advice-givers don’t talk about

"much" - Google News

October 26, 2020 at 05:41PM

https://ift.tt/34rm92L

How much is enough? Less than you think - MarketWatch

"much" - Google News

https://ift.tt/37eLLij

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How much is enough? Less than you think - MarketWatch"

Post a Comment