June 3, 2020 at 7:42 pm ET

-

The low value of payments received by many unemployment insurance recipients jeopardizes the strength of household balance sheets, which in turn may spill over into other sectors of the economy, including businesses who sell to consumers and financial services companies with significant exposure to consumers and households.

-

This analysis relies on self-reported weekly UI benefits, thus providing insight into the value of payments actually received by recipients. For the purposes of assessing risks to household balance sheets, these values are more important than the amount of money they are theoretically eligible to receive.

-

Results from this survey provide little support for concerns that UI benefits augmented by the supplemental pandemic unemployment assistance payments significantly distort the incentives of workers. While some workers may be better off receiving UI benefits than they were while working, the totality of evidence argues that unemployed and underemployed workers receive on balance less money than they did prior to the coronavirus pandemic.

This analysis was authored by Morning Consult Economist John Leer.

Many politicians, policymakers and business leaders have weighed in on the adequacy of unemployment insurance benefits during the coronavirus pandemic. On one hand, they’re concerned that unemployment benefits are not adequate to cover unemployed workers’ bills. On the other hand, they’re worried that UI benefits have become so generous that workers will not return to work. Which is it?

This analysis assesses the adequacy or appropriateness of weekly unemployment insurance payments by drawing on the responses of unemployed and underemployed workers in a wider poll of 2,200 U.S. adults conducted May 19-21. Using proprietary data, it argues that actual UI payments fail to cover basic household expenses for 31 percent of all recipients. Furthermore, there is only limited evidence that UI benefits distort workers’ incentives.

An earlier survey focused on the severe economic challenges posed by misperceptions of unemployment insurance eligibility. This analysis builds on that prior work. Not only do many potentially eligible workers not apply for jobless benefits, but the value of the benefits ends up being inadequate for many workers.

Assessment criteria

From an economic perspective, the optimal value of unemployment insurance benefits satisfies two criteria. First, the value needs to be high enough to cover workers’ basic expenses while they look for a new job in order to prevent unnecessary bankruptcies, insolvencies and financial hardship. Widespread financial hardship harms the entire economy and introduces financial instability, which can lead to severe long-term effects. Second, it needs to be small enough so that workers maintain the incentive to work. If the value of uninsurance benefits larger than workers’ typical income, then few workers lack an incentive to return to work. Economists call this workers’ reservation wage, or the minimum amount of money they need to be paid to induce them to work. The optimal value of unemployment insurance benefits achieves the appropriate balance between these two competing criteria.

Don’t be fooled by a rise in income and savings

The optimal value of UI benefits is a function of individual households’ financial positions (namely, disposable income, savings, wealth, debt servicing and credit availability), non-discretionary expenses and retirement expectations.

Monthly household income and personal savings rate measures produced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis indicate that households’ finances remain strong through the end of April.

According to this data, the current value of unemployment benefits combined with the one-time stimulus check adequately bolstered household balance sheets in April and, therefore, are sufficient to avoid widespread financial hardship. Moreover, they suggest that unemployment benefits may be too generous. The personal savings rate is historically high, and real disposable personal income rose in April. According to this line of thought, if Americans have more disposable income and are able to save so much of it, they must be doing better off financially than they were prior to the onset of the coronavirus.

This view suffers two textbook fallacies. First, even under normal, non-pandemic circumstances, these two monthly measures do not reflect the heterogeneity of households’ financial positions. They are averages of all income and savings in the country. Since incomes and savings rates for some Americans are much higher than they are for others, these averages mask segments of the population that are struggling financially.

When assessing the adequacy of UI benefits, averages provide little insight since they don’t tell us about the distribution of income or savings. These aggregate numbers do not provide insight into the financial condition of UI recipients, which are likely to substantially differ from workers who remain employed.

Second, these are not normal circumstances. The coronavirus pandemic has altered households’ spending patterns. Many consumers have not had the opportunity to make as many discretionary purchases, have opted to defer some purchases or were granted forbearance on their credit card and housing payments.

Households are kicking the can down the road, but they will eventually have to cover these costs. In some cases, deferring the costs may ultimately be more costly than paying them up front. For example, using the supplemental BLS employment situation questions, we found that 19 percent of Americans did not seek medical care for something other than the coronavirus due to the pandemic. In the end, Americans may end up having to spend more in the future than they would have if they had received preventative care sooner.

How much do households receive per week in UI benefits?

A better approach to assessing the strength of household balance sheets is to measure the value of UI benefits relative to UI recipients’ basic recurring expenses.

Each state determines the value of unemployment insurance benefits, both in terms of the weekly payment value and the duration of payment. Weekly payments are typically a function of pre-unemployed income, with higher income workers typically receiving larger weekly checks. In addition, the federal coronavirus relief law, the CARES Act, grants all workers eligible for UI under each state’s system an additional $600 per week.

However, there is a difference between the amount of money that UI recipients are theoretically eligible to receive and the value of their weekly checks. For households trying to make ends meet, theoretical money does not put food on the table. Thus, it is important to know how much money households actually receive per week.

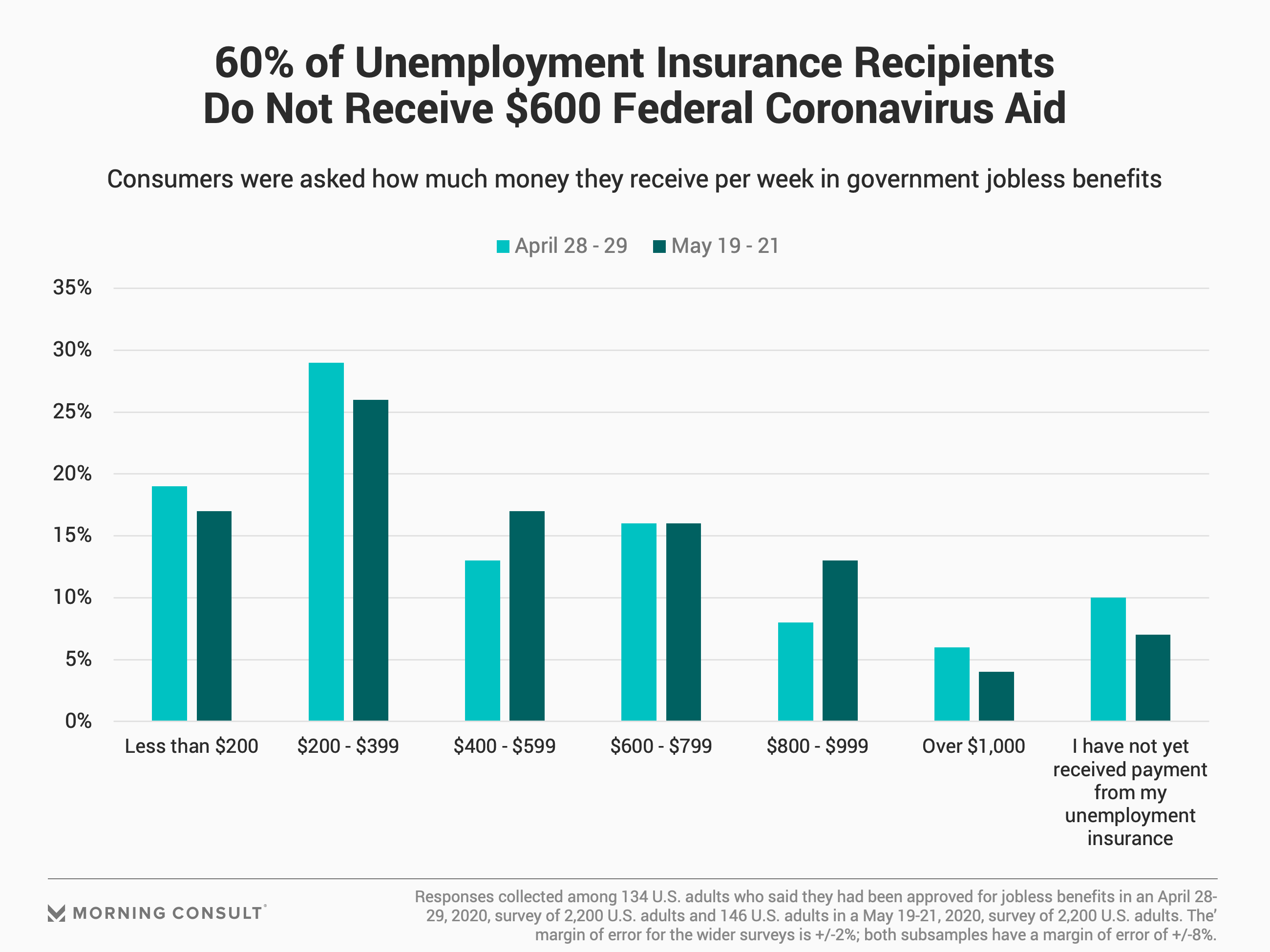

Among the 146 people who said in May that they had been approved for jobless benefits, the distribution of payments is roughly equivalent to what it was in late April: 60 percent of the workers report receiving less than the $600 in federal jobless benefits. This finding is helpful in understanding whether or not UI payments — as actually disbursed rather than theoretically available — can cover basic expenses.

It is also helpful from a policy perspective. The high proportion of workers receiving less than $600 per week calls into question the efficacy of the implementation of the CARES Act. The low rate of supplemental federal payments indicates that the CARES Act is not functioning as Congress and the president intended.

Many households cannot cover basic expenses

The weekly value of unemployment insurance benefits does not cover basic household expenses for 31 percent of UI recipients. An additional 9 percent have yet to receive their first payment.

Forty percent of unemployed and underemployed Americans are at risk of not being able to pay their basic household expenses with their UI benefits. This finding is consistent with 60 percent of UI recipients not receiving the $600-per-week supplement.

Many households depend on employment income or UI benefits to cover their recurring expenses. For 21 percent of American adults, their savings can cover basic expenses for less than a month. That number rises to 24 percent when looking at workers who have had their jobs affected over the past 3 months.

The importance of UI benefit payments is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. Based on the results of a complementary analysis, 70 percent of furloughed and laid-off workers are unlikely to quickly return to their work for their prior employers, and many hourly paid workers are likely to suffer additional financial hardship in the coming months.

When households are unable to pay their basic expenses, they are more likely to fall behind on their debt payments, including student loan, credit card, health care, auto loan, and rent and mortgage payments. When consumers fall behind on these payments, it becomes increasingly difficult for them to catch up: There are very few V-shaped recoveries in personal finances.

It also becomes more difficult and expensive for them to receive credit in the future. From a macroeconomic perspective, such a chain of events increases the likelihood of widespread consumer defaults, which in turn drives down consumer spending well into the future and poses a risk to the economy’s financial stability.

Limited evidence that UI benefits distort incentives

The changes to UI benefits included in the CARES Act may distort workers’ incentives in two ways. First, they may provide an incentive to unnecessarily or habitually apply for UI benefits. In other words, workers who are able to find work may instead claim that they cannot. Second, they may decrease workers’ incentives to rejoin the workforce if they are too generous relative to pre-pandemic incomes.

It’s difficult to measure the extent to which the increase in UI benefits and expansion of coverage to contract workers drove the increase in UI claims. The CARES Act was signed into law on March 27, at the same time as the first wave of UI claims. Additionally, the express purpose for expanding coverage was to increase the number of workers receiving UI benefits. In other words, changing the eligibility criteria intentionally generated a higher increase in the number of UI claims for a given decrease in economic activity.

We see evidence that Americans who applied for UI insurance prior to the coronavirus pandemic were more likely to have applied for UI since Feb. 15, after the onset of pandemic. Among workers who have been laid off, furloughed or had their hours reduced in the past three months and who have previously applied for UI benefits, 57 percent applied again for UI benefits since Feb. 15. Conversely, only 25 percent of workers who have been laid off, furloughed or had their hours reduced in the past three months and had never previously applied for unemployment benefits applied for UI benefits since Feb. 14.

This breakdown of UI applications is a little surprising since the employment effects of the coronavirus pandemic have been so much broader and more severe than past downturns. It may suggest on its face that UI applicants are concentrated among those who know how to “work the system.” However, this relationship should not be construed as causal or as indicating a dependency on or abuse of UI benefits.

Rather, workers who are most likely to have their work negatively affected by the coronavirus pandemic were already the most susceptible to changes in business conditions. In particular, layoffs and reductions in hours are more common among hourly paid workers than salaried workers. Consequently, even before the coronavirus pandemic, among 1,071 employed workers in January 2020, hourly paid workers were twice as likely (22 percent vs. 14 percent) to have previously applied for UI benefits than annual salary workers.

These findings indicate that unemployment insurance functions as intended: Workers most likely to be affected by a downturn in business conditions were the most likely to apply for benefits.

A separate but related question is whether or not the $600-per-week coronavirus relief supplement to UI benefits reduces the incentive of unemployed and underemployed workers to return to work once business conditions improve.

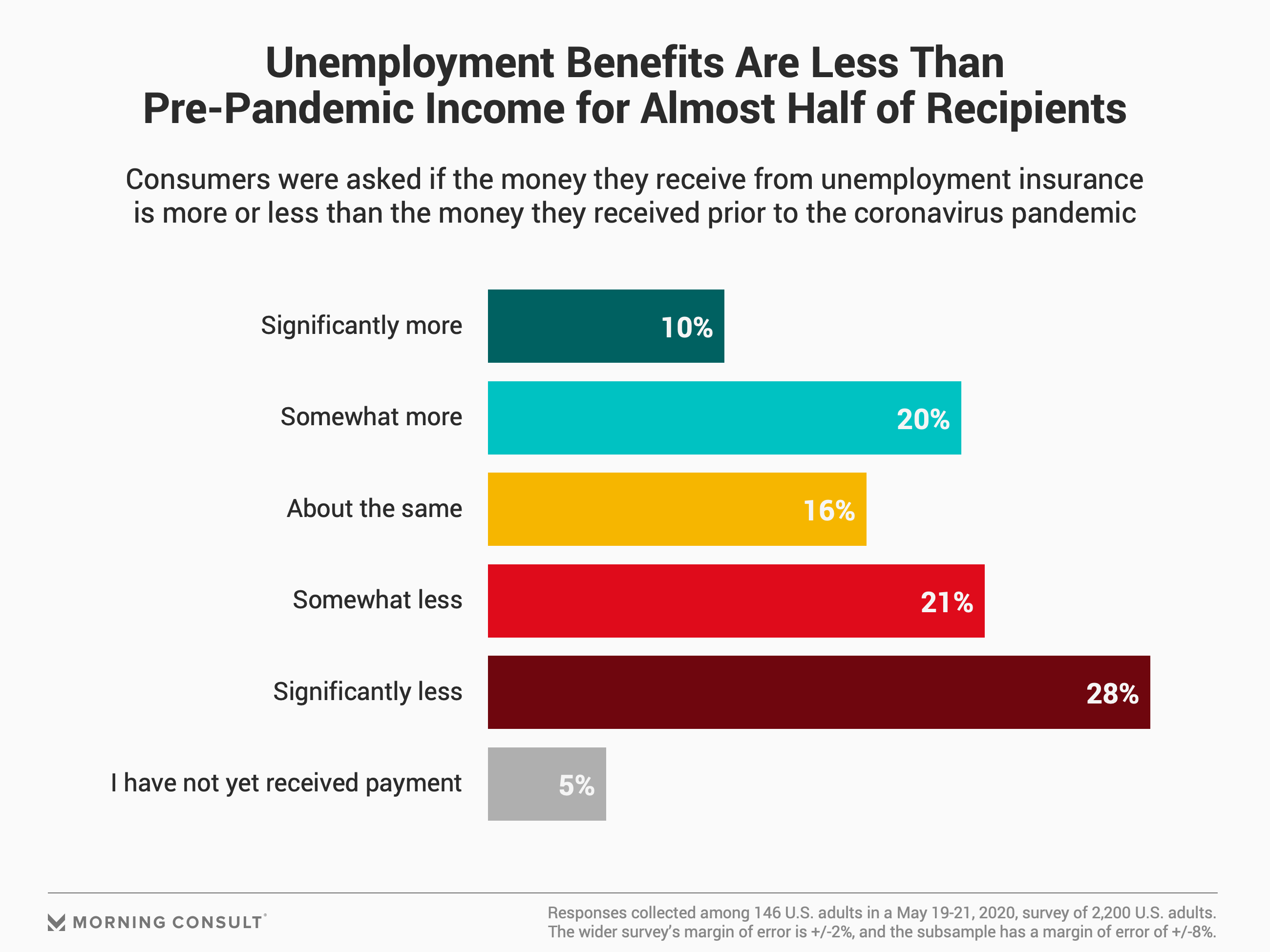

While there is evidence that some workers are earning more from UI benefits than they were from their pre-pandemic jobs (30 percent), a far greater share of UI recipients brings in less than what they made prior to the pandemic (49 percent).

The 28 percent of recipients making significantly less than their income from employment is particularly concerning. These unemployed and underemployed workers are at high risk of facing prolonged financial hardship.

"much" - Google News

June 04, 2020 at 06:42AM

https://ift.tt/3gOMtYJ

Analysis: Are Jobless Benefits Too Much or Too Little for Unemployed Workers? - Morning Consult

"much" - Google News

https://ift.tt/37eLLij

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Analysis: Are Jobless Benefits Too Much or Too Little for Unemployed Workers? - Morning Consult"

Post a Comment