Photographs by Michael Schmelling

Collab day at Clubhouse Beverly Hills was scheduled to start at 2 p.m., but that time came and went and the mansion was still as sleepy as a college dorm on Saturday morning. In one of the house’s four living rooms, an enormous oil painting of George Washington loomed over a pale leather couch. A whiteboard listed ideas for future TikTok videos: shooting range, wine tasting, go-karts, Joshua Tree. Outside, by the sparkling pool, the lawn was studded with statues of Greek gods and human-size hamster balls.

In the kitchen, Casius Dean, an 18-year-old from Hawaii who moved to Los Angeles on his coronavirus stimulus check and is now a full-time photographer at the house, told me that the weekly collab days are an occasion for “people with different levels of social media to create together.” A videographer breezed through on his way to Starbucks. “The girls don’t even have their makeup on,” he said, rolling his eyes. The only one who appeared ready was Teala Dunn, the house’s oldest resident at 23, who was wandering around the mansion in a bright-turquoise bikini. As a child, Teala had played a kidnapped girl on Law & Order: SVU and voiced a bunny in a Disney movie. But those were the old ways to build a career in entertainment. Her TikToks, many of which are about how she has a lot of bikinis but can’t swim, have been viewed more than half a billion times. Teala enlisted Dean to take pictures of her by the pool, where she tossed her hair and tilted her chin at various angles. After a few minutes, she grabbed his phone and squinted at the images. “These are everything,” she said.

A rotating cast of 12 influencers lives in Clubhouse Beverly Hills, their every move documented by three full-time media staff. A real-estate developer, Amir Ben-Yohanan, pays the rent and supplies the creators with whatever gear they need to make content: tripods, ring lights, dirt bikes, pool floats shaped like flamingos. In exchange, the residents make several TikToks a day. “I would compare it to a Hollywood studio,” Ben-Yohanan told me. “The only difference here is the influencers live in the studio.” That, and the movies are a maximum of one minute long.

Teen culture used to be a subset of mass culture; kids may have watched different television shows and movies than their parents, but they were still watching television and going to the multiplex. These days, if you talk to a teenager, you’ll find that they seem to exist in an entirely separate entertainment universe, one in which they’re both the consumers and the producers of the content. As early as 2014, young people were more likely to admire YouTubers than traditional Hollywood celebrities. By 2017, 71 percent of teenagers reported watching three or more hours of video on their smartphone a day. TikTok surpassed 2 billion downloads in the spring, and the pandemic only accelerated its ascendance: As schools closed and children quarantined with their parents, the app claimed an even greater share of teen attention.

Over the summer, TikTok faced an improbable foe, the president of the United States, who, citing privacy concerns, threatened a ban or forced sale of the Chinese-owned app. Yet Donald Trump’s war on TikTok did little, if anything, to slow its growth. In the third quarter of 2020, it was downloaded nearly 200 million times worldwide, more than any other app, even Zoom.

Magazines and gossip websites began covering its stars alongside, or instead of, traditional Hollywood stars. “You don’t see the typical celebrity, because they’re not doing films, they’re not on the red carpet, they’re not doing anything—they’re with their family or whatever,” Morgan Riddle, who was at the time the head of brand development for Clubhouse Beverly Hills, told me in August. “In these content houses, we have a full media team. So in the weirdest way, the pandemic has benefited us in that we’ve all been cooped up and no one has anything to do except make content.”

By 3:30, the house was beginning to fill up with young people, few if any wearing masks. Some came from other creator mansions that are part of the larger Clubhouse family: Clubhouse Next (for up-and-coming creators), Clubhouse FTB (“for the boys”), Not a Content House (an all-girls house for younger creators). Girls brought plus-ones, boys brought plus-ones, plus-ones brought plus-ones. Kids on the cusp of social-media fame had flown in from Georgia or North Carolina to boost their profiles by making content with bigger creators. A tiny girl in ripped jeans, a white crop top, and impeccable makeup turned out to be Coco Quinn, a YouTuber and TikToker who is, according to the Gen Z encyclopedia FamousBirthdays.com, the second-most-popular 12-year-old in the country.

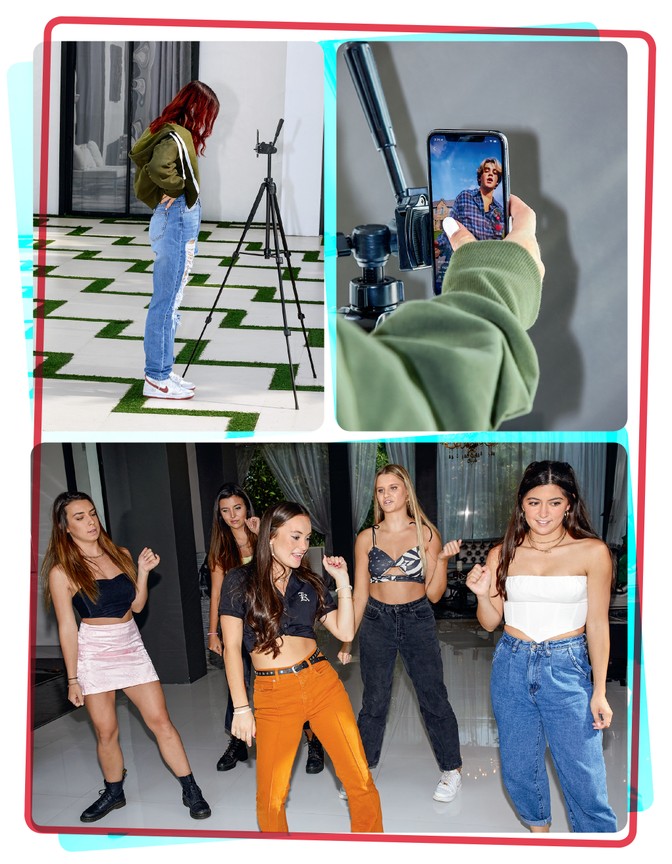

The crowd spilled out onto the patio and the lawn surrounding the pool. The girls claimed the tripods and broke into small groups to film themselves dancing. They wore outfits optimized for movement—sweatpants, crop tops, sneakers. Several of the older ones drank from plastic cups filled to the brim with rosé. They all knew the dance trends that were popular on TikTok that week and performed them over and over again until the energy was right, tweaking the hand gestures to put their own spin on the moves. The air was full of a purposeful, pep-rally enthusiasm. Inside, a catering company served up unlimited poke bowls. Teala watched Coco swivel her hips. “I wish I was 12,” she said with a sigh.

A cluster of boys stood on the patio, discussing legal documents. The influencer contract for one agency was “like 80 pages,” a 17-year-old complained. Another boy was grateful he’d checked with a lawyer before completing his paperwork. “It had me for perpetuity,” he explained. “You have to know what you’re signing.”

The major gossip that day was about Sway House, a content mansion populated by a crew of rowdy, photogenic boys ages 17 to 21. The Sway guys had been hosting enormous parties despite Los Angeles County’s prohibition against gatherings of any kind. One week earlier, the county’s public-health director had warned of “explosive growth” in coronavirus cases among young people; 18-to-29-year-olds had a higher case rate than any other age group. Mayor Eric Garcetti had just disconnected Sway House’s electricity. “Despite several warnings, this house has turned into a nightclub in the hills,” he said in a statement. The house’s most famous member, Bryce Hall, responded by adding a new hoodie to his Party Animal merch line; it featured a shattered light bulb and the phrase lights out.

The Clubhouse collab day, several people assured me, wasn’t a party; it was work. By late afternoon, there were more than 50 people hugging and dancing and laughing, with still no masks in sight. “It’s hard because our job puts us in touch with so many people,” one girl told me. “If you’re in social media, you have to collaborate.”

When a group of boys began jumping off the roof into the pool, I decided it was time to go. More kids were filing into the mansion, and the long driveway was packed with nearly two dozen cars, with more crowding the surrounding street. A masked woman was moving slowly down the sidewalk, writing them all parking tickets.

In November 2017, the Chinese tech company ByteDance acquired Musical.ly, a social-media app whose content consisted primarily of teenage girls lip-synching. Musical.ly was widely considered cringey; the videos were too eager, too nakedly attention-seeking. When ByteDance merged Musical.ly with its own video-sharing platform, TikTok, in August 2018, the newer app was initially tainted with the older one’s reputation. Compilations of awkward TikToks—furries dancing, Goth tweens emoting—circulated on YouTube and Twitter. In a world dominated by a handful of tech companies that tend to either squeeze out or acquire any viable competition, the new app seemed unlikely to expand beyond a niche audience. “I was skeptical. I didn’t know if TikTok was going to evaporate,” Evan Britton, the founder of Famous Birthdays, told me. “I was shocked by how quickly it grew.”

Ahlyssa Velasquez, a redheaded theater kid from Avondale, Arizona, began posting TikToks as @itsahlyssa in 2019, during her senior year of high school. She didn’t mind that people made fun of the app; she felt like an outsider anyway, so who cared? Posting a 15-second TikTok was less work than making a YouTube video and less filtered and posed than Instagram. TikTok videos had a cozy, bedroom vibe (though many TikTokers prefer to film in the bathroom, where the lighting is more flattering). Kids filmed themselves doing what they’ve been doing for ages—singing, dancing, pranking their siblings, mocking their parents—but now they had a potential audience of millions. ByteDance was willing to dig deep to build that audience: The company reportedly spent nearly $1 billion on advertising for TikTok in 2018, largely on other social platforms.

Young women were among the first to cotton on to TikTok’s appeal. At a time when other social-media platforms were embroiled in political scandals, TikTok emphasized fun and entertainment; its stated mission is to “inspire creativity and bring joy” to users. This commitment to lightheartedness can be refreshing as well as disconcerting. When ByteDance was accused of suppressing posts about prodemocracy protests in Hong Kong, the company claimed that there was no censorship—those posts just weren’t as interesting to users as viral dance challenges.

The app’s central feature is the For You page, or FYP, a personalized content feed in the form of an endless scroll of videos. The FYP relies heavily on passive personalization; an algorithm learns what you like by analyzing your viewing patterns and rapidly adjusting the feed to suit your tastes. By watching TikTok videos, you’re training the algorithm to entertain you—and the results are extremely, sometimes uncannily, compelling. The app can seem to know what you want better than you do. Part of the pleasure of TikTok is seeing what unexpected subculture the FYP will serve up for you that day. (Friends and acquaintances I surveyed have recently been steered toward militant-child-socialist TikTok, attractive-ceramicist TikTok, and Draco Malfoy fan-fiction TikTok.) For creators, the app provides sophisticated video-editing tools, as well as a library of sounds and songs to riff on. The platform’s commitment to prioritizing engagement makes it “weirdly meritocratic,” Eugene Wei, a tech executive and blogger, told me. Celebrities and influencers weren’t the only ones getting the views; on TikTok, anyone could go viral.

After her high-school graduation, Ahlyssa went to VidCon, an annual convention in Anaheim, California, for creators and fans of video content. While the big YouTube stars spent much of the weekend talking on panels, the TikTokers had more time to engage with fans. A lot of them asked Ahlyssa to be in their videos; she had distinctive flaming-red hair and a sunny, easygoing disposition—plus, she knew all the dances. By the time she flew home, she had nearly 700,000 followers. Over the course of a weekend, she’d gone from being a fan to being low-key famous.

@itsahlyssa I tried to teach him 😂 @connor.tanner

♬ original sound - celeste 🤎

The content on TikTok is fueled by memes—dance challenges, joke formats, or sound clips that users repeat and parody. To people unfamiliar with the app, TikTok can seem like a bewildering onslaught of trends and in-jokes. This self-referential quality makes it particularly suited to teen culture; watching memes cycle through TikTok reminded me of how swiftly certain pieces of playground lore, like the “pen15 club,” rocketed around my middle school in the pre-social-media era. The memes mutate so quickly that if you log off for a week—or a day—you’ll return to an incomprehensible world. Why is everyone posting about being possessed by an owl? Better, perhaps, to never log off at all.

When Ahlyssa started college at the University of Arizona in August 2019, she got busy with her sorority and stopped posting as much. But then a funny thing began to happen. At parties, drunk girls she didn’t know ran up to her: Oh my God, it’s TikTok girl! The app seemed to have crossed some invisible threshold of popularity. Her sorority sisters were obsessed; when she went home for Christmas break, all her friends wanted to do was post dances. “When Charli started growing big, that’s when it really popped off,” Ahlyssa told me. “Everyone downloaded the app to figure out who this person named Charli was.”

A year ago, Charli D’Amelio lived in suburban Connecticut, in a roomy stone house with homey sayings on plaques in the kitchen. She was a high-school sophomore who loved Judge Judy and scary movies; on weekends, her mom drove her to dance competitions. Then, over the course of a few heady months, she became wildly, inexplicably famous. In March of this year, two months before her 16th birthday, Charli officially became the most popular person on TikTok. As of October, she had 94 million followers on the platform—about 6 million more than Rihanna has on Instagram or Taylor Swift has on Twitter. Now when Boomers want to reach the youth, they call Charli—as Ohio Governor Mike DeWine did in March, enlisting her for a social-media campaign encouraging young people to socially distance. Famous Birthdays’ Evan Britton told me that Charli’s fame is an indication of TikTok’s move from the fringes of youth culture to the mainstream. “J.Lo asked Charli to be in her music video. She’s interested in Charli’s audience, and not vice versa,” he told me. “That’s how you know it’s broken through.”

@charlidamelio dc @marywithoutalamb

♬ Originalton [MARINA - Bubblegum Bitch] - carlamalz

Charli often says that she has no idea why she, of all people, was anointed with TikTok stardom. She downloaded the app in May 2019 at her friends’ urging. Some of her first videos were filmed horizontally—better for showing off traditional dance moves, but not at all how TikTok was meant to be used. She quickly adapted to the app and became one of thousands of girls posting videos of themselves dancing. Two months later, a relatively unremarkable post—a duet, or side-by-side response, to a dance video by @move_with_joy, a woman who makes easy dances—blew up.

The app has had its share of one-hit wonders, but Charli kept adding followers at a rapid clip. Her success was, in part, an accident of timing. Many of TikTok’s earliest stars had cut their teeth on YouTube or Vine, the beloved short-form video app that was shut down in 2017. By mid-2019, though, TikTok had grown enough that it was primed to create a breakout star of its own, and that was bound to happen during the summer, when kids are out of school. (The second-most-followed TikToker, 20-year-old Addison Rae Easterling, posted her first viral video shortly after Charli’s.)

As Charli’s follower count grew, her popularity acquired a reflexive quality; essentially, she became a meme for other TikTokers to react to. There was a flurry of I don’t get why Charli is so popular posts, followed by backlash-to-the-backlash videos tagged #teamcharli and #unproblematicqueen. “It became a runaway feedback loop,” Wei explained. “The more controversy there was about why she was popular, the more popular she became.”

By the fall, kids were coming up to Charli and asking for pictures. Her older sister, Dixie, started posting on TikTok in October and promptly gained millions of followers too. (Gen Z stardom is big on siblings, and particularly twins.) Strangers filmed the family when they went out for ice cream. It was an adolescent’s nightmare/dream—everyone is looking at me. “Every other TikTok rn is about @charlidamelio,” Taylor Lorenz, a New York Times reporter and expert chronicler of Gen Z trends, tweeted last November. That month, Charli switched to an online school that allowed for a more flexible schedule. Soon, Charli, Dixie, and their parents, Heidi and Marc, were traveling to the West Coast nearly every week to hang out with other TikTokers and explore business opportunities. In May, the family—including their four cheerful, extroverted dogs, Rebel, Cali, Cody, and Belle—relocated to Los Angeles.

This summer, I met the D’Amelios at their current home, a starkly contemporary mansion in the Hollywood Hills. In one corner of the open-plan living room loomed a large black sculpture that looked like a shiny fish-man; the kitchen was spotless and intimidatingly white. The real-estate upgrade coincided with a similar update to Charli’s image. On TikTok, I had noticed her looking like a sleeker version of herself, her nails and lashes always done. In person, though, she was soft-spoken and appeared small in an oversize hoodie; I felt acutely aware that she was a child.

When I asked her which milestones had meant the most to her, Dixie piped in: “I feel like 100,000 is the last time you got, like, Oh my God.”

“When did I hit 80 [million]?” Charli said. “Like, yesterday? I cried because I got nervous—why are there so many people …” She trailed off, as if even completing the sentence was too overwhelming. By the time this story is published, she’ll likely have hit the 100 million mark.

Charli’s appeal is tied to her ability to be both relatable and aspirational. She manages to telegraph an ordinary kind of specialness; she’s the pretty babysitter, or the captain of the field-hockey team. (About 80 percent of her followers are female.) Although she’s danced competitively since kindergarten, on TikTok her moves have an offhand, casual quality. People sometimes wonder why more skillful dancers aren’t more famous than Charli, which misses the point entirely—her fans appreciate that she dances in a way that’s approachable.

Charli and Dixie have also deftly managed to avoid scandal. The D’Amelio sisters told me that their careful approach to social media predates their fame. “My friends would post whatever they were doing, and I wouldn’t even post if I went to a party,” Dixie said. “It just kind of worked out in a way that we’ve always been protecting our brands.”

The sisters avoid lip-synching profanities, for the most part, and don’t participate in trends that strike them as questionable, like last spring’s “mugshot challenge.” The week of my visit, TikTok (and the world) was obsessed with “WAP,” Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s delightfully profane song about, well, vaginal lubrication. The most popular dance to the song, which was created by Brian Esperon, a dancer and choreographer from Guam, involved “lots of twerking,” according to Charli, and her mother had declared it off-limits.

“The whole internet wants Charli to do it,” Dixie said.

“I mean, I can do it. I’m just not allowed to … show the people,” Charli said. She looked down and away, and for a minute she seemed like any other teenager teetering between obedience and rebellion.

Dance videos—the dominant form of “straight,” or mainstream, TikTok—have been key to Charli’s rise, and to the success of the platform. TikTok dances fit the constraints of the medium, typically involving front-facing upper-body movements and hand motions referencing the lyrics, sometimes in a playfully naughty way: Draw a heart in the air when lyrics reference love; roll your hips when they’re about getting it on. What you do with your face is just as important as what you do with your body. When I asked Charli what made a good TikTok dance, she answered without hesitation: “Facial expressions.” As she dances, she grins, she purses her lips; for a second, she looks angry enough to hit you, then she breaks into a sweet smile.

Lily Kind, the associate director of the Philadelphia studio Urban Movement Arts, told me that she considers TikTok dance a form of folk dance, drawing from adolescent-girl culture and Black vernacular dance traditions: hand-clapping games like Miss Mary Mack; earlier pop-music fad dances, to songs like “Macarena” and Soulja Boy’s “Crank That”; double Dutch; and even vaudeville-era routines. “It’s engaged and playful with the viewer. It’s all about improvisational composition and one-upping each other—you did this; now I’m going to twist it, flip it, and reverse it. All of that is part of the legacy of Black dance in the U.S.,” Kind said.

The legacy of Black dance in this country, of course, has also been coopted and commodified. This effect is exacerbated by TikTok’s structure, which encourages a kind of contextless sharing and repurposing and, at its worst, the 21st-century minstrelsy known as “digital blackface.” “If you look at some of the dances on TikTok—the Mop, the Nae Nae, the Hit Dem Folks, the Woah—they were dances that young Black folks have done in parking lots, at cookouts, at home. Then they fall into the TikTok hemisphere and become something else,” says Michele Byrd-McPhee, the founder and executive director of the Ladies of Hip-Hop Festival.

Last December, Charli saw a TikTok of two kids dancing to the Atlanta rapper K Camp’s “Lottery (Renegade).” She hadn’t seen the dance before and assumed they had made it up. “I did the guy version of the dance, and I guess that caught on,” she told me. The Renegade was more complex and faster-paced than many TikTok dances; after Charli’s post, it became enormously popular. High-school students held Renegade dance battles. Lizzo did the Renegade; so did Kourtney Kardashian and her son, and Alex Rodriguez (badly) and his daughter. Videos tagged #renegade have been viewed 2.2 billion times.

Though Charli never claimed credit for coming up with the dance, it became informally associated with her. The dance’s creator was actually Jalaiah Harmon, a Black 15-year-old from suburban Atlanta. Like Charli, Jalaiah had taken dance classes from a young age, and regularly filmed herself dancing in her room. She was goofing around before dance class one day when she came up with the Renegade choreography. She posted it to Instagram, where it got several thousand views. The dance eventually made its way to TikTok, where it arrived without context or credit, another meme appearing from the void. Jalaiah felt both proud and frustrated as she watched it take off. “I was commenting under people’s posts, telling them I made the dance, but they didn’t really believe it, because I didn’t have much of a following on TikTok,” she told me.

As the dance continued to spread across the app, Jalaiah claimed credit for it in a video that gradually gained traction. When Taylor Lorenz told Jalaiah’s story in the Times, Charli’s comments were flooded with people accusing her of being a thief. But Jalaiah wasn’t out to shame Charli so much as let the world know the dance was her invention. “Jalaiah has always defended Charli. The way TikTok was set up, it was hard to figure out who started” the Renegade dance trend, Stefanie Harmon, Jalaiah’s mother, told me.

Getting credit has made a meaningful difference in Jalaiah’s life; she’s since been hired to work with Samsung and American Eagle, and appeared on The Ellen DeGeneres Show and in a music video for Sufjan Stevens. In February, Jalaiah, Charli, and Addison Rae Easterling attended the NBA All-Star Game and posted a video in which they all did the Renegade; a few hours later, Jalaiah performed the dance during the halftime show.

Kudzi Chikumbu, TikTok’s director of creator community, told me that the company is working on better ways to attribute original dances. In the meantime, the Renegade scandal has inspired users to come up with their own solution: citing dance creators in video captions. “Now it’s so normalized; when you do a dance, you give credit, and if you don’t know who made it, then you just ask,” Charli said.

This year, the D’Amelios have focused on establishing themselves as the first family of TikTok. Marc, an entrepreneur and onetime Republican candidate for the Connecticut state Senate, has more than 7 million followers; his TikTok bio now identifies him as “CEO of The D’Amelio Family.” Heidi, a former model, has more than 6 million followers. Their brand—nice, relatable family!—doesn’t seem far from reality; in person, they have an easy affection for one another. Casius Dean, the Clubhouse photographer, told me that he’d recently had dinner with the D’Amelios. “I haven’t felt a home environment in so long,” he told me, sounding wistful. “It made me forget about social media for a minute.”

Unlike some young TikTokers who are negotiating the world of viral fame more or less on their own, Charli has benefited from having business-savvy parents. “I work in New York City,” Marc told me. “I’ve been around brands my entire career.” The family has signed with United Talent Agency, which manages its growing ventures. In October, the co-head of UTA’s digital-talent division announced that he was leaving the agency to become president of D’Amelio Family Enterprises, the family’s attempt to establish itself as a media company. Between them, the D’Amelio sisters have a podcast, a book, a hit single, and several ad campaigns. Charli, who has repeatedly pledged her love for Dunkin’ in unsponsored posts, now has a signature drink at the chain (cold brew with whole milk and three pumps of caramel swirl). This summer, Forbes estimated that Charli and Dixie were the second- and third-highest-earning TikTokers, after Addison, netting an estimated $6.9 million from mid-2019 to mid-2020.

That’s a lot of money, though it’s a fraction of what J.Lo makes in a year. Eager, perhaps, for the kind of recognition, and remuneration, that older entertainment media can provide, the family has started documenting their lives in professionally filmed and edited YouTube videos that feel like test runs for a future reality-TV show. A recent video tracked Charli’s quest to get Dixie a pair of $32,000 Dior sneakers for her 19th birthday. The video involves classic reality-TV plot points (a prank, a surprise reveal), but Dixie doesn’t externalize her reactions; instead, she gets quiet. The more I watched their YouTube videos, the more I realized that both sisters, though they are accustomed to opening their lives up to viewers, still have a slightly interior quality, some part of their personalities that they keep to themselves. This seems good for their mental health, although not, perhaps, for ratings.

Shortly after my visit, Charli posted two versions of the “WAP” dance. In the first, she doesn’t appear at all. Instead, the camera is trained on her friends’ faces. We’re meant to understand that she’s offscreen, doing the dance for their delighted, scandalized eyes only. In the second, she performs a slow, balletic interpretation of the dance. The videos were peak TikTok—savvy, creative, playful. They’ve been viewed more than 100 million times each.

A couple of years ago, Amir Ben-Yohanan, the Clubhouse investor, noticed that his four kids were “obsessed,” first with Musical.ly and then with TikTok. “Like many adults, I looked down on it. I thought they were just messing around, dancing. It didn’t seem very serious,” Ben-Yohanan told me. When his family moved to Los Angeles in 2019, though, he began to meet people who had turned social media into a lucrative career. “It seemed to me like the Gold Rush, like the Wild West,” he said. And as far as he could tell, the kids were running the show: “They were doing everything, creating the content, engaging in brand deals, doing the marketing, doing the PR.”

Hype House, a content house that Charli and Dixie were briefly affiliated with, is a prime example. The loose collective of about a dozen teenagers and 20-somethings rented a Hollywood mansion late last year; within weeks, videos tagged #hypehouse had more than 100 million views. Since the heady days of Vine, influencers have seen the benefit of living and working together. But TikTok, where fame arrives swiftly and is particularly social, pushed the trend into overdrive. “When you have three people in a video together, that’s what users want—the content does so much better,” Evan Britton explained. “Traditional Hollywood wasn’t like that. People might’ve acted together, but they didn’t need to be together for their brand.”

Life at Hype House looks like a teenage dream. Members appear to make a living off flirting, dancing, and pranking one another; their jobs are, essentially, to maintain their popularity. No one ever seems to cook; the house gets 15 or 20 Postmates and Uber Eats deliveries a day. The group’s relentlessly viral posts helped establish the aesthetic of straight TikTok—young, pretty, mostly white people dancing. (The platform has many stranger, older, less white, queerer, and more absurdist pockets, though they tend to get less traction.)

Shortly afterward came Sway House, the content mansion of “dudes being guys,” as Bryce Hall has put it. While straight TikTok’s version of femininity—sweet, coy, lots of bare midriffs—is familiar, the Sway guys veer from fratty aggression to “eboy” sensitivity to boy-band earnestness to ambiguously ironic homoeroticism.

TikTok’s popular crowd cemented its fame this spring, when everyone else was stuck at home. I can trace my own overconsumption to late March. The more I was afraid to leave my house, the more I became unexpectedly invested in the love lives and shifting friendship alliances of TikTok’s young stars: Were Dixie and Noah a thing? Did Addison unfollow Bryce? My own social universe offered no gossip; of all the pandemic losses, this was the most trivial, but I nonetheless felt it acutely. The TikTokers stepped in to fill that void. “The drama has been popping off way more during quarantine, for sure,” one of the teenage founders of First Ever Tiktok Shaderoom, a popular social-media gossip account, told me. There were breakups, angry neighbors, arrests, lawsuits—all of which fed the content machine. “It’s like back in the day with the Kardashians on TV. The audience knew every week there’s going to be something crazy that goes down,” Josh Richards, one of the founding members of Sway House, told me.

The popular kids of TikTok project an image of easygoing fun and success. Part of the pleasure of their videos is the implicit promise that you, too, could be just a viral moment away from joining them, hanging around a mansion and earning money by posting content. An influx of kids has moved to L.A. to make a go of it.

Ben-Yohanan, who had no previous experience in Hollywood, said he started the Clubhouse group as an attempt to professionalize the booming content-house scene. Even so, it’s sometimes hard to know who, if anyone, is in charge. Many young influencers are managed by people barely older than they are. At least one Clubhouse manager is just 20; TalentX Entertainment, the company behind Sway House, is run in part by grizzled veterans of new media, which is to say 23-year-old YouTubers.

Earlier this year, Ahlyssa Velasquez dropped out of the University of Arizona to focus on making TikTok videos full-time. She was the first influencer to move into Clubhouse Next, which was decidedly less glam than Clubhouse Beverly Hills—10 residents shared the five-bedroom house. As house manager, she was responsible for getting everyone out of bed and keeping track of everyone’s content quotas. “People think, Oh she lives in this big mansion and just posts 15-second videos,” she told me. “It’s a lot harder than it looks.”

And the margins are leaner than you might think: While TikTok may have captured Gen Z’s attention, brands have been slower to advertise on the platform, and the fees they offer for promotional TikToks are typically less than what they pay on Instagram. Influencers with 1 million TikTok followers can make about $500 to $2,000 for a sponsored post. After seven months, Ahlyssa left Clubhouse Next, which was dropped from the Clubhouse family because it didn’t generate enough revenue.

In the old model of celebrity, stars were propped up by studios and agencies with a stake in their enduring appeal. TikTok’s young stars have grown up in a world where fame can arrive in an instant, but also disappear overnight. Trends come and go swiftly; even platforms don’t last. (The 21-year-old Bryce, who got his start on the live-streaming platform YouNow six years ago, has already outlasted three of the sites where he used to post.) A few TikTok creators are being assimilated into larger, older, more stable forms of media; others will hustle to keep up until they lose touch, or just lose interest.

I spoke with Ahlyssa this fall, when much of California was on fire and Trump was once again threatening to ban TikTok. Terms of a potential deal with Oracle got more convoluted by the day. Ahlyssa told me that she wasn’t following the story too closely. She had been on TikTok for only a year and a half, but she was already nostalgic for the old days, before posting was her job, before all of her friends were influencers. Back then, she would scroll through her FYP and see all sorts of different people doing all sorts of different things. Back then, the app had felt like an engine of surprise and delight—anything could happen, anyone could blow up. Now it felt like the same people over and over again: Charli, Hype House, Addison, Sway House. She loved them all, but maybe it would be good if everyone had to start fresh. “TikTok is the platform I started on,” she said, “but I’m ready for the next one.”

This article appears in the December 2020 print edition with the headline “The Hardest-Working Kids in Show Business.” It was first published online on November 20, 2020.

"how" - Google News

November 21, 2020 at 01:05AM

https://ift.tt/2KtnGxK

How Charli D'Amelio Took Over TikTok - The Atlantic

"how" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MfXd3I

https://ift.tt/3d8uZUG

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How Charli D'Amelio Took Over TikTok - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment