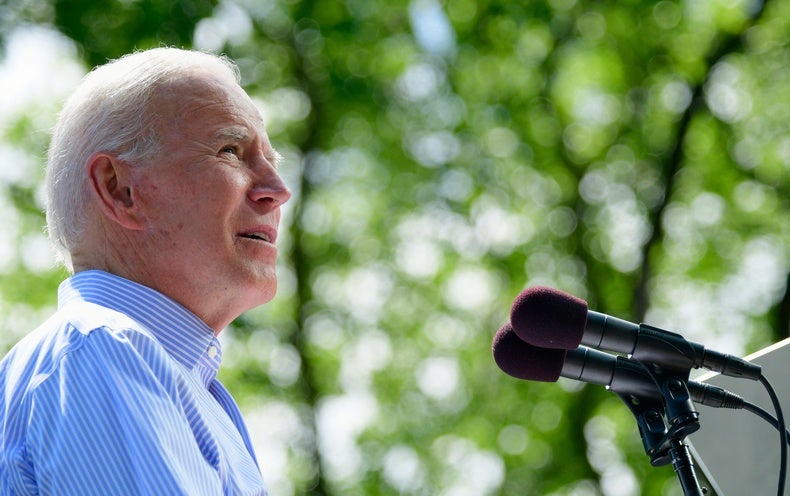

If Democrat Joe Biden defeats President Trump this November, his EPA will have a blank slate for writing climate rules.

Because the Trump administration spent three and a half years demolishing its predecessor’s Climate Action Plan, Biden’s team would have an opening to update rules for carbon, methane and hydrofluorocarbons that would exceed their Obama-era counterparts or be more tailored to the political, judicial and economic realities of the 2020s.

To be sure, a departing Trump EPA would leave finalized rules for power plant carbon, vehicle fuel economy, and oil and gas development, among other things, but most of those regulations haven’t faced court reviews, allowing an incoming administration to ask that they be returned to the agency.

That request—if granted—would clear the path for a Biden EPA to write new rules to go with the former vice president’s promise of rejoining the Paris Agreement and the global effort to contain global warming.

If November’s election also results in a Democratic Senate, that chamber’s leaders could use the Congressional Review Act to quickly rip up rules finalized in the second half of this year, such as EPA’s forthcoming standard for emissions from oil and gas production, which is expected this month.

The Clean Air Act is likely to be the main vehicle for a Biden EPA to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, just as it was for the Obama and Trump administrations. But the rules will likely differ in stringency from Trump’s. And since President Obama left office, the Democratic Party has moved left on climate change with the introduction of the Green New Deal and stepped-up warnings by scientists who say warming must be kept below 1.5 degrees Celsius, instead of 2 degrees.

After taking fire during the primary from advocates who saw his climate platform as lacking in ambition, the presumptive Democratic nominee has embraced more progressive goals—including in the plans he outlined yesterday (Greenwire, July 14).

“Biden is campaigning very much to the left of where the Obama administration stopped,” noted Kevin Book, managing director of the consulting firm ClearView Energy Partners LLC.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has succeeded in moving the courts to the right, up to and including the Supreme Court. Justice Anthony Kennedy, the swing vote who retired from the court two years ago, usually sided with the court’s liberal members on environmental cases like Massachusetts v. EPA, which established that EPA has the authority and obligation to address climate change under the Clean Air Act. The two justices Trump has nominated don’t have that reputation.

“Believe me, this Supreme Court is no friend of the environment,” said David Bookbinder, chief counsel at the Niskanen Center and one of the attorneys who litigated Massachusetts v. EPA.

Power plants

One of the biggest open questions about a Biden EPA’s climate program is how it might treat carbon emissions from power plants. The Trump EPA finalized its rollback of Obama’s Clean Power Plan last summer, replacing it with the much more limited Affordable Clean Energy standard.

Litigation on ACE will likely be ongoing next January, and if Trump is no longer president, EPA could decline to defend the rule and ask the D.C. Circuit to remand it to the agency for review. If it does, it could begin work on a new one.

A task force of supporters of Biden and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) last week proposed that the U.S. power sector should become carbon neutral by 2035 (Climatewire, July 9).

But experts are split on what that new rule should look like.

David Doniger, senior strategic director of the climate and clean air program at the Natural Resources Defense Council and another Massachusetts vs. EPA litigant, said the Biden team should use the opportunity to put in place a rule with tougher targets than the Clean Power Plan, which aimed to cut carbon 32% compared with 2005 levels by 2030.

Those reductions are happening even without the Obama-era rule. The best illustration of the limited impact last summer’s Clean Power Plan repeal has had on the power industry’s outlook can be seen in the Trump EPA’s claim that the ACE rule—a modest heat-rate improvement rule—would cut emissions 30% by 2030. Virtually all of those reductions would occur without the regulation simply because of the sector’s market-driven move from coal to gas.

“It’s not enough, but it shows that you could go a lot further under the Clean Air Act at a very reasonable cost in a second version of the Clean Power Plan,” Doniger said.

EPA staff in the waning days of the Obama administration were in fact looking at ways to strengthen the Clean Power Plan.

But other experts say the Obama-era rule had potential legal problems that were never tested in court and could still be rejected. A Biden EPA should take the opportunity to reconsider its approach, they argue.

In the Clean Power Plan, EPA interpreted the Clean Air Act’s mandate to reduce emissions through the “best system of emissions reduction” as extending to the broader power grid rather than applying narrowly to emissions on-site at individual power plants.

The Supreme Court never weighed in on that interpretation, but Bookbinder said the current court would be unlikely to sign off on EPA’s expansive reading of the statute.

Instead, he proposed that EPA double down on on-site reduction requirements, including mandates that coal-fired power plants switch to gas—which they can burn anyway—and retire when they reach the end of their useful lives.

“There are ways to do power plants that are not just heat-rate improvements on a plant-by-plant basis,” he said.

Richard Lazarus, a Harvard Law School professor and author of “The Rule of Five,” which chronicles Massachusetts vs. EPA, said the agency under Biden would be aggressive. But he agreed that a conservative Supreme Court would be a barrier.

“They will try to do more on power plants under a less ambitious legal theory,” he predicted, adding that that would probably mean on-site emissions reductions.

Book said market forces and state mandates had been effective at greening the power grid without a strong federal standard. Since 2015, when the Clean Power Plan was finalized, transportation has overtaken power generation as the U.S. sector that contributes the most to climate change, he noted.

‘Methane first’

Book predicted that a Biden administration would promulgate a “very muscular” set of methane rules for oil and gas facilities.

Trump’s EPA is set to kill Obama-era methane controls later this month, but Book said the rules could come back stronger in a new administration, although with greater compliance flexibility.

Democrats have rebranded methane as a “superpollutant” in recent years—a term that previously applied only to hydrofluorocarbons that are thousands of times more climate-forcing than carbon dioxide compared with methane’s 80% premium over two decades. Book sees that as a signal.

“If they win, methane first and everything else behind it,” he said.

Book predicted that EPA would then pivot quickly to Obama’s unfinished work of regulating existing sources that are responsible for the overwhelming majority of the sector’s leakage.

The Democrats’ Biden-Sanders task force has already signaled that reversing Trump’s vehicle standards, replacing them with stronger standards and granting California’s waiver to implement its own car rules would all be priorities.

“Democrats affirm California’s statutory authority under the Clean Air Act to set its own emissions standards for cars and trucks,” the task force’s plan states, adding that EPA would collaborate with the state, trade unions and others on standards.

“I think there’s no doubt that the Biden administration would come in and revoke the SAFE rule and do its own rulemaking to set CO2 emissions standards for cars and trucks,” said Jeff Holmstead, a former EPA air chief, referring to the current Department of Transportation fuel economy standard.

But while he said there is “no question" that a president would have the authority to ask DOT and EPA to jointly promulgate a greenhouse gas and fuel economy standard like the one implemented under Obama, it would prove harder to use the Clean Air Act to regulate other sources for climate change.

“When it comes to stationary sources, I think they’re going to struggle to come up with something that’s meaningful,” said Holmstead, who now represents industry clients at Bracewell LLP.

The air quality law allows for cap and trade, but under a section that is better suited to local hazardous pollutants than to global greenhouse gas emissions, he said.

Other experts said that a Biden administration could move beyond reinstating and building upon Obama’s climate program by regulating high-emitting sectors like manufacturing for the first time.

Carbon rules for oil refineries and manufacturing languished on EPA’s Unified Agenda for much of the Obama administration without much visible progress despite their contributions to climate change.

But Bookbinder said Biden should announce plans to promulgate “very very severe” rules for new sources in those sectors early in his presidency.

“Make it very clear that a two-term presidency or a Biden and some other Democratic presidency was going to be seeing a lot of the industrial sector brought under CO2 regulation,” he said.

That approach might even generate interest in climate legislation, he said.

Reprinted from Climatewire with permission from E&E News. E&E provides daily coverage of essential energy and environmental news at www.eenews.net.

"how" - Google News

July 22, 2020 at 12:46AM

https://ift.tt/2ZOD5xM

How a Biden Administration Could Reverse Trump's Climate Legacy - Scientific American

"how" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MfXd3I

https://ift.tt/3d8uZUG

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How a Biden Administration Could Reverse Trump's Climate Legacy - Scientific American"

Post a Comment